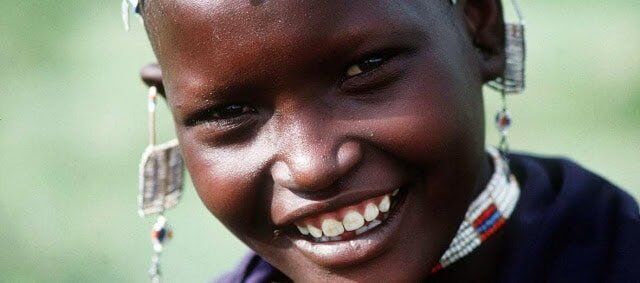

The Masai as Conservationists

Recent reports have cast the Masai people in a negative light, suggesting they are responsible for poaching and other forms of wildlife exploitation in Africa. This perception is both misleading and damaging, as it disregards the Masai’s longstanding commitment to sustainable coexistence with nature. In this article, we’ll address these misconceptions and highlight the Masai’s critical role as conservationists in East Africa.

Misleading Accusations of Masai Involvement in Poaching

In a recent radio broadcast from ABC Australia, it was implied that Masai tribesmen were responsible for the death of an elephant, claiming, “the spears and poisoned arrows used to fell this elephant point to Masai tribesmen” (PM, October 11, 2013). Locally, the Tanzanian National Parks Department mentioned in its publication that lion populations in Tarangire National Park were “threatened by Masai attacks” but noted that the situation was stabilizing (TANAPA Today, October 2010).

This portrayal has left tourists and the general public with a skewed view of the Masai, leading many to believe they are hunters or involved in systematic poaching. However, these claims distract from the real issues, such as conflicting conservation policies, the expansion of private game reserves, and the global demand for ivory and animal products, which are the true drivers of East Africa’s wildlife conservation challenges.

Setting the Record Straight on Masai Culture and Conservation

The Masai are found primarily in northern Tanzania and southern Kenya, living a nomadic, pastoralist lifestyle that they’ve maintained for centuries. Unlike some claims, the Masai do not engage in hunting or trade in bush meat. They are primarily herders of goats, cattle, and sheep, rotating grazing areas to allow the land to regenerate—a system that benefits both domestic and wild animals.

Their traditional grazing lands overlap with some of East Africa’s most biodiverse regions, including the Serengeti, Ngorongoro, and Tarangire in Tanzania, as well as the Masai Mara and Amboseli in Kenya. In these areas, the Masai have coexisted peacefully with wildlife for generations. Wildlife encounters, while rare, are typically resolved with non-lethal tactics like making loud noises or calling park rangers to deter intruding animals.

For more insights on life in Tarangire, check out our guide to What Is Staying in Tarangire National Park Like?.

Conservation Partnerships and Community Governance

In April, seven Masai communities bordering Tarangire National Park partnered with the Tanzanian government to establish the Radilen Wildlife Management Area, a legally protected 580-square-kilometer reserve. This new conservation zone is free from hunting, charcoal production, and permanent settlements, effectively expanding protected land by nearly a fifth of the adjacent park’s size.

Historically, this area was protected under private leases as early as 1993, when efforts to drive out illegal poachers, farmers, and charcoal burners began. With the establishment of eco-tourism ventures, these communities have provided safe haven to one of Africa’s fastest-growing elephant populations. Conservation has also brought economic benefits, with user fees generating revenue that funds schools, medical dispensaries, and water projects within Masai communities.

The Role of Community Governance in Conservation

One of the defining traits of Masai culture is its complex system of self-governance, which helps maintain social harmony and prevent illegal activities like poaching. The Masai’s leadership structure is highly effective at addressing issues that may threaten their way of life. Poaching is a self-defeating activity that would be swiftly addressed by community leaders, as it contradicts the Masai’s long-held values and their interest in preserving the environment for future generations.

The Masai are not only conservation allies but essential partners in protecting East Africa’s wildlife. The growing threats to African elephants and other species have led to a surge in funding for various protection programs, but these efforts are often most successful when the Masai are actively involved. It’s their land, their heritage, and they are among the best-equipped to safeguard it.

For more information on African conservation efforts, you might enjoy reading The Best Places to See the Big 5.

The Masai are far from the poachers they are sometimes unfairly painted to be. As pastoralists and stewards of the land, they have developed a sustainable coexistence with nature that many conservationists are now trying to emulate. Working in partnership with the Masai is not only respectful but crucial to the long-term preservation of East Africa’s iconic wildlife. By setting aside land, implementing effective community governance, and embracing eco-tourism, the Masai have shown themselves to be committed conservationists. Their involvement is vital for the future of African wildlife, and they deserve recognition, not blame, for their dedication to protecting it.